FLEETING FUSION WITH A FURBALL (for National Cat Day, October 29, or any day)

Have you ever been transformed by contact with an animal? Intuitive communicator Marta Williams observed, “Animals have a unique way of affecting our hearts. They sidle in closer than humans do.” That’s been true with our dogs, and there’s also a special awe I feel when I see or interact with wild critters.

In 1995, when our family lived in Evanston, Illinois, I heard of an event at DePaul University to raise money for the care of abandoned and abused big cats. Partly due to the movie, “The Lion King,” which had just come out the year before, our nine-year-old and six-year-old were immensely interested in big cats, so we went to the fund-raiser. Our younger girl wore her favorite pants, with Simba the lion on the thigh.

We thought we’d see real lions and tigers in cages, but arrived to find them close at hand, walking around a large room with handlers guiding them on leashes. Apparently, the animals had been recently fed because adults were allowed to approach the big predators! Children, understandably, were warned away. (They could be seen as bite-size prey.)

We kept our distance and perused the informative displays along one side of the room, learning about Big Cat Rescue, Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge, and the university’s wildlife program. We noticed people lined up on the other side of the room to see a young tiger, so we joined the line. Just as we approached the chair where a woman held a four-month-old tiger named Sherman, he started to squirm and snarl.

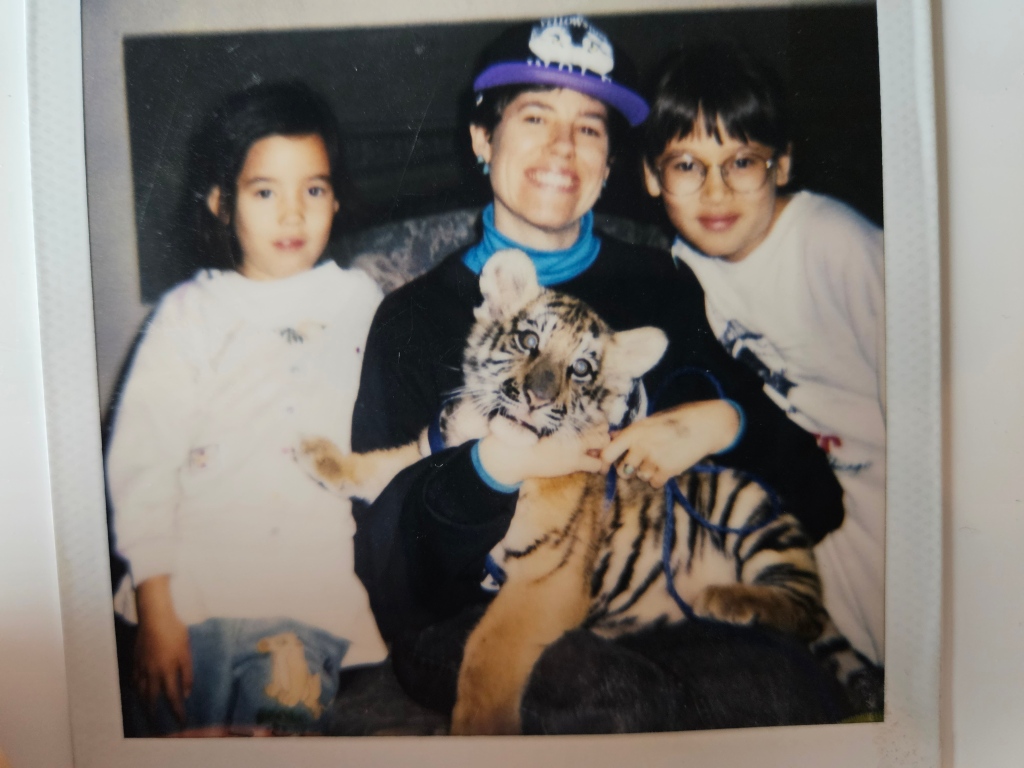

“Sorry, I think Sherman needs a break,” the woman said, holding a leash as she set the tiger down. She started to walk away, then paused when the young tiger walked over to me. She looked at me and asked if I’d like to sit down and hold Mr. Grumpy. In less than a heartbeat I was in her chair, arms out. Our daughters sat on each side of me, and I held Sherman, feeling a fleeting fusion with the wild as he settled into my lap. It was a happiness like no other.

“He calmed down,” his handler observed with a smile. My turn was quickly over as others stepped up to hold the curious cub.

Checking my journal for that day, October 29, 1995, I saw a two-sentence entry, as if my words were inadequate for what had happened: I held a four-month-old tiger today. I cannot go back to the way I was.

Barbara Wolf Terao is the author of Reconfigured: A Memoir, published by She Writes Press in July. She and her husband, Donald, live on an island in the Salish Sea near their children, who were not, after all, eaten as tiger snacks. Author website: barbarawolfterao.com (Originally posted on Storied Stuff 10/29/23)

This is Buttons, our daughter and son-in-law’s cat, who has a wild side of his own. (The trucks belong to our grandson.)