It’s all about territory and who lays claim to it. Moles dig tunnels underground and live generally solitary lives. If the tunnel of one mole breaks into the tunnel of another, a fight to the death ensues. As Marc Hamer wrote in his surprising memoir, How to Catch a Mole, “Fighting is in the nature of things with territories.”

That sentence got me thinking about habitat destruction and its role in the novel coronavirus pandemic sweeping across the world. What is an animal’s habitat if not a territory? Every species, and every community within each species, needs a territory, a place to call home. Looking under “W” in our World Book Encyclopedia, I read, “Conflicts over resources are the most basic and enduring causes of war. Resources include land, minerals, energy sources, and important geographical features. The world’s first wars probably were fought over resources.” That’s about as basic as you can get. When we violate the homes of our fellow creatures, they may not consciously go into battle with us, but the environmental and health consequences can be as dire as any war. After all, humans aren’t the only inhabitants of this planet, though we sometimes act like it.

Many of the worst viruses affecting humans are transmitted from bats, birds, and other animals. Epidemiology research shows that COVID-19, the source of our current contagion, with new fatalities every day, can be traced back to bats and possibly pangolins. We encroach on their environments or capture them for market, and thereby expose ourselves to new combinations of germs to which we have no immunity.

There is a story called Who Speaks for Wolf that has stayed with me for two decades now. In the face of our COVID-19 pandemic, it comes to mind once again.

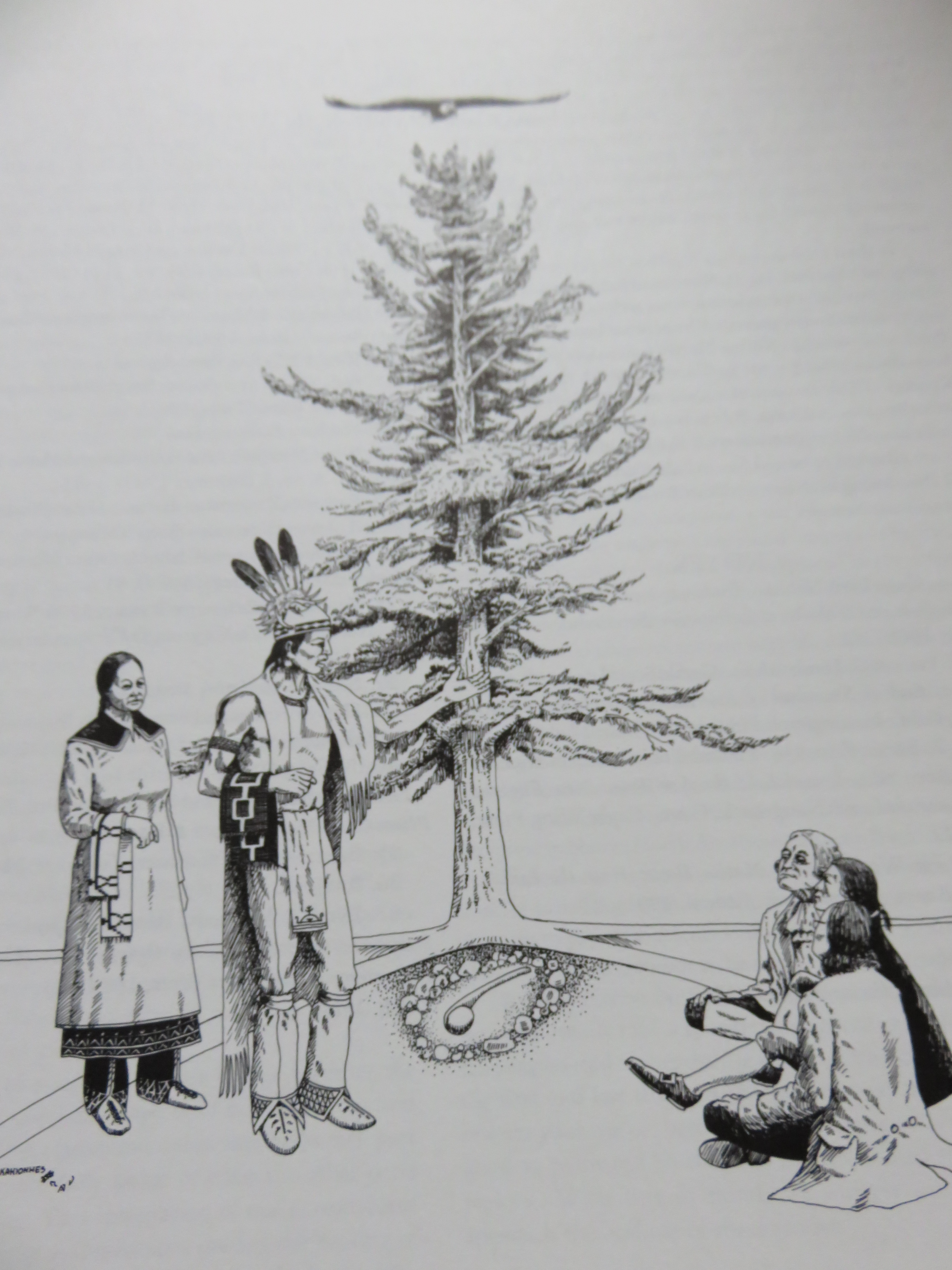

The story begins as some people outgrow their living space and seek out a new one. In Paula Underwood’s way of sharing this oral history, she wrote, “Long ago Our People grew in number so that where we were was no longer enough.” Runners “were sent out from among us to seek a new place where the People might be who-they-were.” (I have added punctuation here and there to Paula’s words. She used very little.) A site was found that had space for the longhouses and for the Three Sisters of corn, beans, and squash. After much discussion, it was decided to move the community to this site.

As work began on the new site, a man called Wolf’s Brother returned to the village. “He asked about the New Place and said at once that we must choose another” because, “You have chosen the Center Place for a great community of Wolf.” Further, he warned, “I think that you will find that it is too small a place for both and that it will require more work then- than change would presently require.” This man was well known for understanding the ways of wolves and his words were respected but overruled, because the establishment of the new village had already begun.

“The People closed their ears and would not reconsider,” Paula wrote. When all was prepared and the people moved in, the People, as Wolf’s Brother predicted, had to constantly contend with Wolf. It was a challenge to protect their children and their food. “They soon discovered that this required so much energy that there was little left for winter preparations.” After trying this and that, they came to the question of the final solution, which was to kill off the wolves.

This is an ongoing question for human beings right now. Do we need to take over every corner of Mother Earth? More species become extinct or endangered every day. Is this the kind of people we want to be? Is this the kind of world we want?

In the story, Paula put it this way. “They saw that it was possible to hunt down this Wolf People until they were no more.” Such a thought gave them pause. “They saw, too, that such a task would change the People: they would become Wolf Killers, a People who took life only to sustain their own, would become a People who took life rather than move a little. It did not seem to them that they wanted to become such a people.”

In hindsight, the People wished that Wolf’s Brother had been included in the decision-making from the beginning. They admitted, “To live here indeed requires more work now than change would have made necessary.” From that time on, they included a question in every discussion, before a decision was finalized, “Tell me now, my Brothers. Tell me now, my Sisters. Who Speaks for Wolf?”

Wisdom comes from such challenges as these, when we take an honest look at the chain of cause and effect in which we have participated and make new decisions. We can broaden our perspectives and listen to a diversity of data, putting our heads together for better solutions.

Paula Underwood preserved the tale taught to her by her father and wrote it down as one of Three Native American Learning Stories (2002, A Tribe of Two Press). Before Paula’s death in 2000, many people studied with her in the high country of New Mexico or among the redwoods of California. She was a mentor to me and reminded us, through her stories and aphorisms, to listen to all species, not just our own. She invited us to listen to trees and wind. And our own minds.