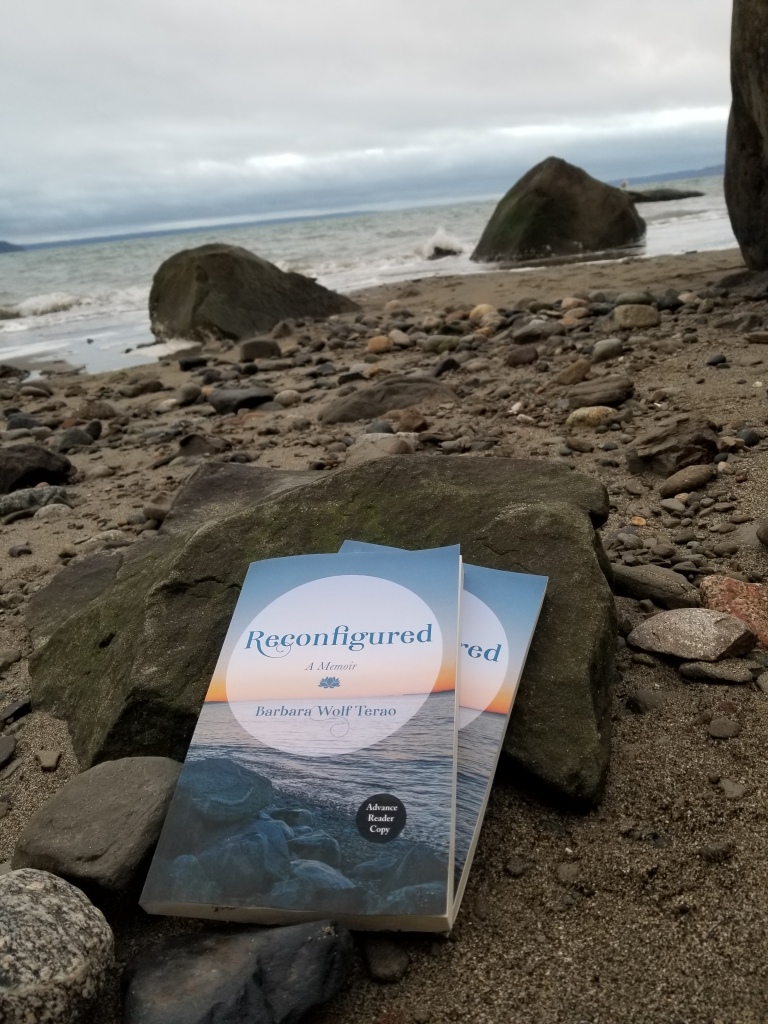

Barbara Wolf Terao

A guest post for Women Writers Women’s Books on the process of writing my memoir. So many of us think we are too ordinary or too weird to write about ourselves, yet once we start writing and sharing, we may be surprised by how many people appreciate our stories!

Urgency of the Story

Before there were podcasts, there were call-in radio shows, and listeners would often identify themselves as “long-time listener, first-time caller.” Similarly, I’m a long-time writer, first-time author, and it really has been a long time!

I began a youthful writing practice when my parents gave me a blue “journal” (actually, a record-keeping account book) for Christmas when I was eleven. Alongside the candy cane in my stocking was a pen. Already showing signs of being a tormented author, the first thing I wrote in my journal on December 29, 1967, was “Dear Journal, I should’ve written sooner.”

Keep Writing

Writers are not required to be procrastinators. It’s not part of the job. But it seems common among us creative types—until we are seized by an urgency to get to work. I was a sporadic writer with the notion that “someday” I’d write a book.

I write nonfiction and an occasional poem. The first topics I tried to turn into books twenty years ago had to do with the power of nature and the power of Indigenous teachings. I even had a month-long residency at Ragdale in Illinois to focus on those projects. But then such impressive books about nature, such as Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, showed up that I relinquished my plan. I did, however, write a grad school dissertation about intercultural learning called Indigenous Ways of Knowing. Yet, as a European American, I felt it best to leave the topic up to Native Americans to speak for themselves.

Then, starting in 2017, my circumstances became so dire and compelling I felt I had to lay them out for my own understanding and, I hoped, for the encouragement of others. I had moved from the Midwest to live alone on an island in the Pacific Northwest, and—less than four months later—I was diagnosed with cancer.

Daily Practice

By the time I recovered physically and emotionally from cancer and its treatments, there was a pandemic that kept me isolated at home. Millions of people were struggling to cope and endure during the spread of a sneaky and often deadly virus. I had some things to say about those kinds of struggles, so I sat down at my desk one day and decided, “I’m a working writer.” I’d aspired for decades to write a book and now I was going to make it a reality by showing up at my laptop to write my way toward synthesis and understanding. There was no need for contrite apologies of “I should’ve written sooner,” because I was butt-in-chair almost every day for a year, until I had something I could show to an editor.

You Are Enough

Author and writing teacher Phillip Lopate observed that people generally feel they are either too weird or too boring to write about. I wouldn’t say I’m unusually weird, but I do have my own perspectives on life that I want to articulate on the page. You might be surprised how much you have to say, once you get going!

Cancer was not a story I wanted to tell; rather, it was overcoming disease and weathering rough storms I wanted to talk about— to muster the courage of both me and my readers. Finally, at the age of 60, I had enough serious, humorous, and spiritual material to fill a couple hundred pages.

This is how I learned to write a book: By writing it, especially learning to write scenes and dialogue. This is also how I learned a whole lot about myself. As memoirist Linda Joy Myers wrote, “Memoir writers have to undergo a major deconstruction of self while learning how to construct a book!”

A professor on the island where I live read an advance reader copy of my memoir and told me he could relate to my story because he has cancer. Now, he said, he doesn’t feel so alone. A woman who is a breast cancer survivor wrote of how she drew inspiration and guidance from reading my book: “The ways Barbara copes with her reconfiguration can benefit anyone going through changes.” With affirmations like that, I’m ready to start my next book!

This was my tale to tell. You have yours. The urgency of the story leaves no time to waste.